How the US Removed Mobutu from Power

When asked, Museveni misled many people by explaining that he went into the Congo to overthrow Mobutu's corrupt regime. While that might have ended up being one of the byproducts of the overthrow of Mobutu, the real reasons were different. To appreciate the real reasons why Museveni and Kagame were involved in overthrowing Mobutu, we need to understand the US involvement in the Congo since the country became independent in 1961.

When asked, Museveni misled many people by explaining that he went into the Congo to overthrow Mobutu's corrupt regime. While that might have ended up being one of the byproducts of the overthrow of Mobutu, the real reasons were different. To appreciate the real reasons why Museveni and Kagame were involved in overthrowing Mobutu, we need to understand the US involvement in the Congo since the country became independent in 1961.

Given the strategic minerals found in the Congo, the country was of prime interest to the super-powers (the US and the former Soviet Union). Guided by the concern about the domino theory, the US had an exaggerated view of the communist threat in Africa, fearing that if Zaire, renamed the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) fell under communist influence, the surrounding countries would follow suit. Consequently, they viewed Lumumba, the first Prime Minister of the Congo as a communist and therefore, a threat to US interests. Acting on this false premise, the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) organized the assassination of Lumumba and his replacement by their stooge, Col. Mobutu, who renamed the country Zaire.

In 1975, while on a safari around Africa, President Valery Giscard d'Estaing, negotiated with Mobutu several cooperation agreements which transferred Zaire from the “tutelage” of the US to France. Zaire fell under the influence of France, which did not go well with the US prompting the US to seek ways to restore its influence in Zaire.

In the late 1990s, the US had two objectives in the Congo: clip the wings of France as they did in Rwanda and more importantly get rid of Mobutu who had become an embarrassing relic after the cold war ended.

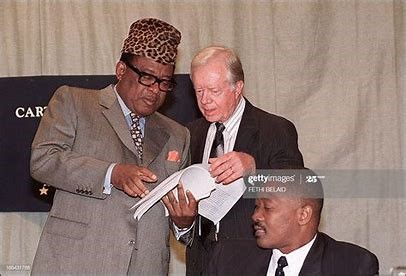

Mobutu’s relationship with the US began to deteriorate shortly after his June 1989 visit to Washington, D.C. He was given accolades for his apparent great success in facilitating a peace settlement in Angola at the summit of 18 heads of state in Gbadolite just before he left for Washington. Unfortunately, the Gbadolite agreement fell apart. Around that same time, the US Congress was expressing serious concerns about human rights violations in Zaire and seeking to link military and economic aid to respect for human rights. (The image shows Mobutu with President Carter when relationship was still not as bad).

Mobutu’s relationship with the US began to deteriorate shortly after his June 1989 visit to Washington, D.C. He was given accolades for his apparent great success in facilitating a peace settlement in Angola at the summit of 18 heads of state in Gbadolite just before he left for Washington. Unfortunately, the Gbadolite agreement fell apart. Around that same time, the US Congress was expressing serious concerns about human rights violations in Zaire and seeking to link military and economic aid to respect for human rights. (The image shows Mobutu with President Carter when relationship was still not as bad).

In March 1990, James Baker, the US Secretary of State, attended the Independence ceremonies of Namibia. On his way back he stopped over in Kinshasa where he delivered a stern warning to Mobutu to improve his records on human rights. From September 8 to 14 1992, US Vice President, Dan Quayle, made a highly publicized five nation tour of Africa. Whereas previous Vice Presidents from Hubert Humphrey to George Bush would have included a stopover in Kinshasa, Dan Quayle skipped it.

To make matters worse, Kinshasa's worst violence in more than 30 years broke out just a week after the Quayle snub. The Zairian army rioted over pay. For two days, soldiers joined by civilians, looted shops in the city center and suburbs, which forced foreigners to flee across the Congo river to Brazzaville. France and Belgium flew in more than 1,000 troops to evacuate their citizens. By September 30th, the US had evacuated 830 Americans from Brazzaville. Several hundred other foreigners made their way to countries bordering Zaire.

The Assistant Secretary of State for African Affairs, Herman Cohen, told the Senate Subcommittee on Africa that, "Zaire needs a functioning government that can restore order, begin the long process of economic recovery, and lay the basis for a democratic system”. He added that, "Recent events have proved beyond doubt that the present regime under President Mobutu has lost legitimacy to govern Zaire during the transition to democracy”.

While Herman Cohen stopped short of calling for Mobutu to leave the country, arguing that Mobutu still had a role to play until election, Senator Paul Simon, Chairman of the Subcommittee on Africa asked the Bush administration to persuade Mobutu to leave Zaire after turning over power to an interim government. The New York Times echoed the call in its editorial of November 20, 1992 headlined, "Mobutu must go", proclaiming that such "a nudge was long overdue".

On January 29 1993, the State Department Spokesman, Richard Boucher, revealed that President George Bush had sent Mobutu three letters over the past ten months, urging him to turn over all effective power, particularly over economic and financial affairs, to the transitional government that had been selected by the recently concluded national conference.

When appearing before the Senate Foreign Relations Subcommittee on Africa on June 9th, the new Assistant Secretary of State for African Affairs in the Clinton administration, George Moose, explained that the situation with Mobutu was "part of the tragic consequences of the Cold war era" when policies of the US were influenced by broader geo-political strategic considerations. He noted that what was currently strategic was totally different from before. He revealed that the Clinton administration was working with the Belgians and the French to increase political and economic pressure on Mobutu, including visa restrictions and prohibition of arms export. He also revealed that though stronger measures were being considered, no official action to oust Mobutu was yet taken.

In March 1992, the Clinton administration withdrew its ambassador to Zaire, Melisa Wells, and declared that she would not be replaced until Mobutu stopped blocking the transition to democracy. It was obvious that Mobutu had to leave and that the United States was committed to ease his departure. This would follow precedents set in the previous two decades when Washington facilitated the political retirement of several dictators who were its close allies. They included the Shah of Iran, Somoza of Nicaragua, and Marcos of the Philippines. So, ridding Zaire of Mobutu was just a question of how to implement the decision. However, having learned lessons from Somalia, the US did not want to involve its own military. Instead, they supplied their proxies (Rwanda and Uganda) with weapons and intelligence to do the dirty job.

The incentive for the Kagame regime to go along with the US plan was to avenge Mobutu’s help to the old Rwandese government and to eliminate the threat of armed attacks by Hutu fighters based in Zaire. Museveni was motivated by the opportunity to ingratiate himself to the USA, ensure the safety of the Kagame regime he helped install in Rwanda, eliminate any threat of Ugandan guerrilla fighters based in eastern Zaire, foment ethnic cleansing in northeastern Congo and lastly, to loot the natural resources of the Congo for which Uganda was found guilty by the International Criminal Justice.

In the end, both the US and its two allies, Kagame and Museveni, achieved their individual goals when they toppled Mobutu from power. Unfortunately, that left Zaire mired in a heap of problems which are still plaguing the country today.

This is an abridged version of the full article originally published in the UPCNet in 2016.